What is economics? A question that many of us have and all of us have different definitions and suggestions. Is it about money? Is it about numbers? Is it having a magic ball and trying to tell the future?

Probably all of them are correct to some extent and wrong in some others.

For me, economics is always going to be the art of observing the changes in our society. A combination of history, law, policy and sociology that, with the support of some numbers, explain how our world is working, the problems humanity is facing and why. A long endeavour to make suggestions on how to improve people's lives and deal with social injustices and inequalities.

I know I know, it sounds much more romantic than probably mainstream economic courses have already told you. But economics is not the cruel, boring mathematical discipline that some people believe.

Let's start from the beginning and the father of modern economics, Adam Smith. You may have heard of him, about his theory of the “invisible hand” and that his work inspired the free markets we have at the moment. Yes I know that there are a lot of opinions about the benefits and negatives of free markets, but let’s take a step back and notice what Adam Smith observed.

His book “The Wealth of Nations” describes the trade system of the time between ‘mother nations’ and their colonies. Under this system the mother nations restricted the trade opportunities of the colonies with other nations, that has as a consequence the colonies to pay higher taxes, exporting most of their valuable resources to the mother nations and being allowed only to import products from the mother nation at high prices. As a result, the mother nations became richer while the colonies didn’t get the same benefits. Those observations of Adam Smith made him suggest that a less restrictive trade relationship would allow both the colonies and mother nations to flourish without creating inequalities.

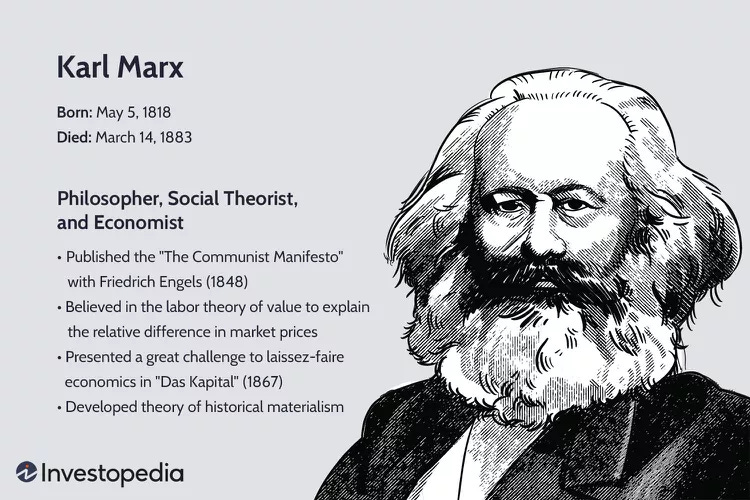

Inspired by Adam Smith’s work, Karl Marx in his work “Das Kapital” observes the capitalist system, explores how profit is made and explains labour economics. His observations about the relationship of the workers with their employers in a very tense period of history during the industrial revolution are particularly interesting; despite all the benefits of the machine to the production and economic growth, the industrial revolution brought bad living conditions for the factory workers, exploitation of workers and rising inequalities. In simple terms, what Marx observed was that the system of the time put this new working class in a position where they could survive only if they could find work.

So economists so far have made observations on the trade system, labour markets and inequalities, but can they predict wars? One of them, John Maynard Keynes, one of the most influential economists of modern history, wrote after the end of what was then called the Great War a book called “The Economic Consequences of the Peace”. In that book he suggested that the punishing war reparations that the Allies demanded from Germany would have negative consequences for people and lead to the rise of populism. He ended his book with the following paragraph:

Economic privation proceeds by easy stages, and so long as men suffer it patiently the outside world cares very little. Physical efficiency and resistance to disease slowly diminish, but life proceeds somehow, until the limit of human endurance is reached at last and counsels of despair and madness stir the sufferers from the lethargy which precedes the crisis. The man shakes himself, and the bonds of custom are loosed. The power of ideas is sovereign, and he listens to whatever instruction of hope, illusion, or revenge is carried to them in the air. ... But who can say how much is endurable, or in what direction men will seek at last to escape from their misfortunes?

Not too many years later. Adolf Hitler was to write in Mein Kampf:

What a use could be made of the Treaty of Versailles. ... How each one of the points of that treaty could be branded in the minds and hearts of the German people until sixty million men and women find their souls aflame with a feeling of rage and shame; and a torrent of fire bursts forth as from a furnace, and a will of steel is forged from it, with the common cry: "We will have arms again!"

As we all know a Second World War happened with catastrophic consequences for Europe and the rest of the world. To avoid repeating the same mistakes, Keynes was one of the architects of the Marshall Plan, a plan not very different from what he suggested after the end of World War 1. The Marshall Plan helped aid to assist in the rebuilding of Europe, Allies and Axis countries alike – except for the Soviet Union, which refused to participate, and its Eastern European satellites, which were blocked from receiving aid by the Soviets.

These are only a few examples about how economists’ work is more about the art of observing. All three examples, despite their political differences and the assumptions we have about them, observed the societies they lived in, the human nature, the consequences of political decisions, the relationships between societal groups with the main goal in their mind to make people's lives better. That is my passion for economics at least and the reason I am writing these blogs.

And I would like to finish this blog with my favourite quote about who and what a economist should be, from Keynes in his obituary essay for his teacher Alfred Marshall:

The master-economist must possess a rare combination of gifts …. He must be a mathematician, historian, statesman, philosopher — in some degree. He must understand symbols and speak in words. He must contemplate the particular, in terms of the general, and touch abstract and concrete in the same flight of thought. He must study the present in the light of the past for the purposes of the future. No part of man’s nature or his institutions must be entirely outside his regard. He must be purposeful and disinterested in a simultaneous mood, as aloof and incorruptible as an artist, yet sometimes as near to earth as a politician.

PS. I would like to dedicate this blog to all my economics lecturers in both Greece and Scotland - thank you for giving me comprehensive knowledge, teaching me things outside the textbook and assisting me to be an unorthodox economist.