The cost of being a woman

If you are one of these unorthodox economists with a passion for economic history like me, you would have been delighted to learn on Monday morning that Claudia Goldin was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economics for her work on women’s pay.

Believe it or not Goldin is only the third woman awarded a Nobel Prize in economics since 1969, making her success even more significant if you consider the reasons why she received it. As many media articles described it is a win for many :)

Goldin is one of those brilliant economists that combines traditional labour market economics with economic history to explore how women’s position in employment changed over more than 200 years in the US.

One of Goldin’s main findings was that despite all the changes that the economy has faced in the 20th century such as higher economic growth and higher proportions of women employed, the gap in earning between men and women has hardly closed.

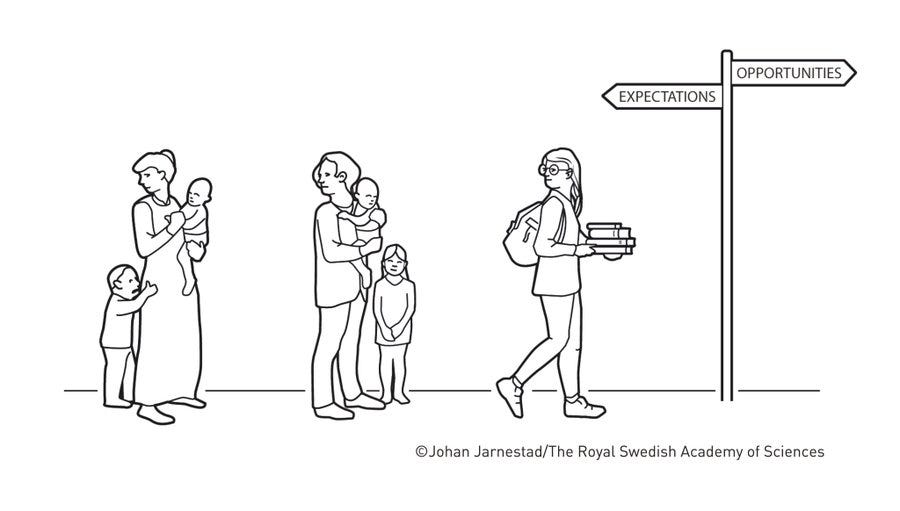

Usually education and occupational differences may explain the gap in earnings between men and women, however Goldin’s research finds that there are other factors that play a vital role in the gender pay gap, which have to do with early education choices, the arrival of the first child or the availability to work extra hours.

Education choices and expectations

Goldin mentions that in the early 20th century women were expected to leave their jobs after marriage so they concentrated on taking care of the family, a factor which dominated their education and career choices. Even when the expectations about women changed marginally in the second half of the century; married women could return to the labour force if their children were older, still they had to rely on the education choices of the past which underestimated their career potential.

And as Goldin mentions the exit of work for a long time after marriage “also explains why the average employment level for women increased by so little, despite the massive influx of women into the labour market in the latter half of the century.”

One factor that gave the opportunity to women to plan better their career was the introduction of birth control pills. The “Power of the Pill” influenced education and career choices for women, with them achieving higher education rates. However this wasn’t enough to remove the gender pay gap, though it became “significantly smaller since the 1970s”.

Arrival of the first child

Goldin also revealed that at the moment, earning differences are between men and women in the same occupation and they start widening from the arrival of the first child. According to research from the Institute of Fiscal Studies, the evidence shows that there is a “child penalty” for women in regards to their earnings, while the average earnings of men are almost completely unaffected by parenthood!

Having a child is not a small task, pregnancy and childbirth are tremendously taxing on the body, and can take a long time to recover from—both physically and emotionally. Infants need constant attention, and high childcare costs put women in a position where they have to make difficult decisions about their career. And the longer a woman stays home, even if she works part-time, the less optimistic her future prospects and earning potential become.

Greedy jobs

Lastly in her latest book Goldin speaks about “Greedy Jobs” as an explanation of the gender pay gap. These jobs, which raise earnings inequalities, reward individuals that are willing to work long hours, which has as a result higher hourly pay or bonuses. However, if you decide to be on parental duty, support your work life balance and be there for your children, you face a career penalty.

Gender pay gap in the UK

But let’s have a look at what is going on in the UK. According to ONS the gender pay gap has been declining slowly over time. Over the last decade it has fallen by approximately a quarter among both full-time employees and all employees.

Note that the gender pay gap is calculated as the difference between average hourly earnings (excluding overtime) of men and women as a proportion of men’s average hourly earnings (excluding overtime). It is a measure across all jobs in the UK, not of the difference in pay between men and women for doing the same job.

In 2022, the gap among full-time employees increased to 8.3%, up from 7.7% in 2021. Among all employees, the gender pay gap decreased to 14.9%, from 15.1% in 2021, but is still below the levels seen in 2019 (17.4%). The gender pay gap for all employees is considerably larger than the full time and part time gaps as a larger proportion of women are employed part-time, and part time workers tend to earn less per hour.

The important fact from the UK statistics is that the gender pay gap varies according to age. For people in their 20s and 30s, the gender pay gap is not existent or negative, but when among the full time employees that are over 40, the gender pay gap increases significantly.

And this is some of the empirical evidence that support Goldin’s theory in the UK; as women after the age of 30 decide to become mothers and they spend longer time outside of work, their earnings and career opportunities face a hit.

Despite Goldin’s work not providing any policy recommendations, it is a vital tool for us to understand the roots of the gender pay gap and how countries like the UK can address it, or how other countries in an earlier stage of development can put in the cornerstones of a more equal society.